Eostre And The Matronae Cult

Historical Evidence And Modern Fairy Tales.

There are many untruths about the origins of the neo-pagan spring festival of Ostara as well as its namesake the elusive Eostre; a goddess who may or may not have existed before the nineteenth century.

When I first came across Eostre I did not believe that she was a goddess, but instead the simple misunderstanding of an Anglo Saxon monk who was witnessing the early days of Britain’s conversion to Christianity. Over the centuries, this misunderstanding grew into an elaborate tale about a spring goddess who transformed a dying bird into a hare to save its life. I soon discovered, however, that things were not as clear cut as I had originally thought. So was it possible that Eostre was indeed a goddess that was honoured by the Anglo Saxons at the spring equinox?

The first piece of evidence begins with the Venerable Bede, a 7th century scholar and monk of the early Christian church who wrote of the Anglo Saxons, ‘Eosturmonath (the Anglo Saxon month for April) has a name which is now translated Paschal month and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month’. As with his mentioning of Mothers’ Night, this is Bede’s own interpretation and has not been proven or generally accepted.

This is the only written evidence we have that mentions an Anglo Saxon goddess called Eostre which has led some people to question Bede’s credibility as no other Germanic or Scandinavian myths, images or even Medieval texts exist of her. Yet Bede had no reason to fabricate a heathen deity in order to explain the name of Eosturmonath considering he would have wanted to stay well away from any pagan associations. Could Eostre have simply been the name of a spring festival and not an actual goddess?

The Anglo Saxons named all of their months, apart from the two that Bede says were named after goddesses, after seasonal weather conditions, customs or calendar events. Bede wrote that not only was Eosturmonath named after a goddess, but Hrethmonath (March) was as well. If these goddesses were so important, in the eyes of the Anglo Saxons, to have had months named after them, then why do we not know a single thing about them apart from a few lines written by Bede himself? Maybe these months were in fact just like all of the others and had names that simply reflected the time of year.

The word ‘hrethe’ can mean fierce, harsh and rough, which does describe the weather in March or is ‘Hretha’ an actual war goddess, as suggested by Kathleen Herbert in her book ‘Looking for the Lost Gods of England’? There is written evidence of a tribe called the Hrethgotan or Hreda’s Goths, but I believe that this name just means ‘fierce Goths’ rather than a tribe that called themselves after a war goddess. As for Eosturmonath, Ronald Hutton believes it is not named after a goddess. In his book ‘Stations of the Sun’ he says. ‘Estor-monath’ simply meant the ‘month of opening’ or the ‘month of beginnings’, and that Bede mistakenly connected it with a goddess who either never existed at all, or was never associated with a particular season but merely, like Eos and Aurora, with the dawn itself.’

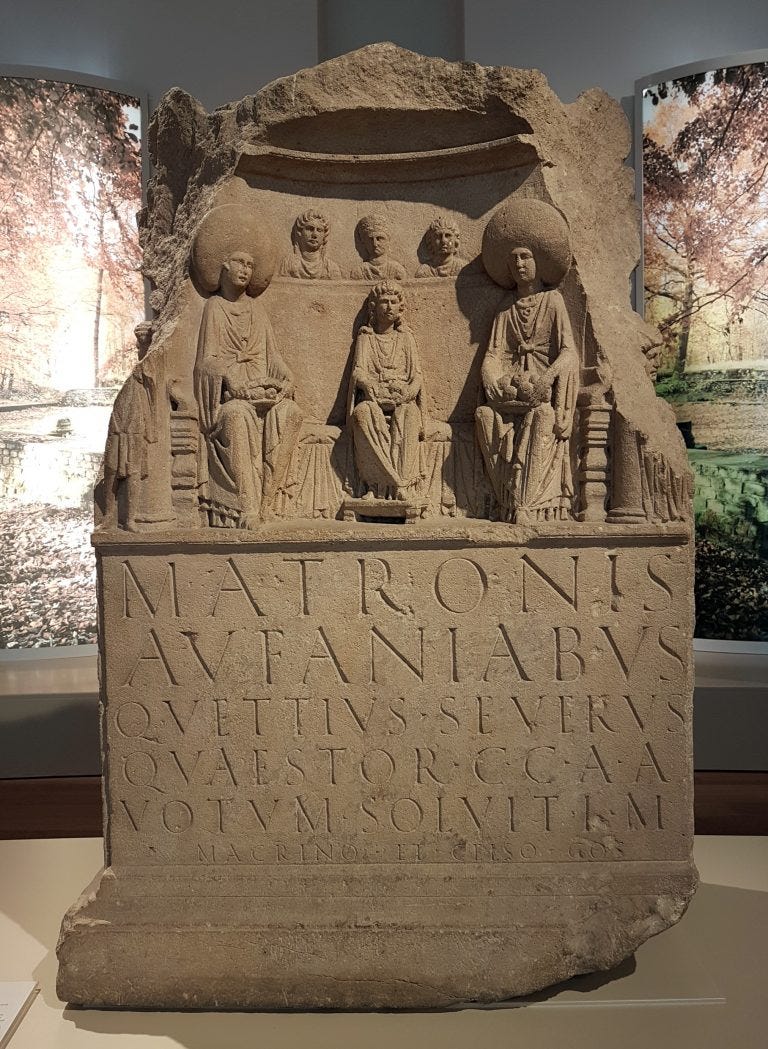

In his book “Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World”, Philip Shaw explains that both Hretha and Eostre were goddesses local to Kent, a county in the south east of England where Bede gathered most of his information from. If this is the case then it might explain why no other traces of Eostre or Hretha have been found. Shaw goes on to say that Anglo Saxon missionaries took these names with them when they travelled to what is now France and Germany. He also makes a connection between Eostre and the Matronae Austriahenae Cult. Matronae translates to ‘mothers’ and it is thought that Austriahenae means the ‘Eastern Ones’.

Eostre, Ostara and Austria are cognates descended from a common Proto-Indo-European root meaning ‘to shine’. In English, ‘east’ and ‘eastwards’ come from the Proto Germanic adverb of this root which expresses movement towards the rising sun.

Sadly, we know very little about the Matronae Austriahenae, a mother goddess cult that was venerated in Britain in the regions of Kent, Wessex and Northumbria as well as Francia and Frisia on the continent. Around 150 ‘Austriahenae Stones’ have been found in these areas, where Roman soldiers were stationed, bringing their Matronae Cult with them. We do know that the Frisians began settling in Kent from the 3rd century onwards when salt water flooding destroyed their farmland, again bringing their religious beliefs with them. The linguistic, archaeological and historical evidence surrounding Eostre does point towards her possible veneration in eastern England, the same region as the ‘Austriahenae Stones’ (if of course Bede was right). I will now take a quick detour to the Rhineland in Germany where over 1500 Roman inscriptions and reliefs have been discovered dedicated to the Matronae so that we can get a better picture of what it was like to worship The Mothers.

The mother cult in the Rhineland has been linked to a Germanic tribe known as the Ubii. Dating between 150 and 250 AD, the reliefs generally depict three women; the middle woman as a young maiden with an older woman either side of her. Even though the evidence is Roman it is extremely likely that the worship of these goddesses stems from a much older Germanic cult. We can surmise that there were similarities between these two mother cults as Roman soldiers were crossing over to Britain at this time along with traders and people migrating.

A religious community made up of the Ubii and the soldiers grew out of the Roman military’s presence in the areas of Cologne, Bonn and Eifel. The Romans' relationship with the Ubii was a mutual one. They offered the Ubii protection, especially from the Suebi tribe and in exchange they expected loyalty to Rome which of course allowed for their military advancement into other territories. The Matronae Cult’s development was helped by the soldiers and veterans’ wealth because they were able to invest in the building and carving of altars, temples and votives. Whenever Roman soldiers occupied a new area they hoped to not only win over the people but also the people’s deities. Soldiers would have continued to make offerings to their own gods to stay connected to their homeland but also to local deities for protection.

Marriages between Roman soldiers and Ubian women coincided with the rise of the Matronae Cult, which suggests that women played a role in introducing the Matronae to the soldiers. There is evidence from some of the altar remnants that there was a female priesthood. There are depictions of female attendants and female processions as well as women offering platters of fruit while holding garlands (the garlands were a Roman influence).

The Matronalia, a festival that took place on the first day of the Roman year honoured Juno Lucina, the goddess of childbirth and motherhood.

In her book ‘Winters in the World’, Eleanor Parker explains that during Bede’s time, each region was its own kingdom with its own dialect, which meant that there were variations of how the months of the year were named. In some areas the month of March, for example, was known as Hylda. So to what extent did this change the meaning of March? Was Hylda also a ‘local’ goddess or something completely different?

Another piece of evidence comes from Einhard (770-840) a Frankish scholar, historian and close adviser to Charlemagne. Einhard’s work entitled ‘The Life of Charlemagne’ (c830) chronicles his twenty three years of service in the powerful emperor’s court; an emperor who succeeded in uniting most of western and central Europe under his rule and who fought against the Saxons. Charlemagne Christianised the Saxons on penalty of death and destroyed all of their idols. He even changed the Saxon names of the months. So if Eostre was genuinely a Germanic goddess then why would a fanatical Christian emperor name the month of March ‘Ostarmanoth’ when all he would have wanted was to destroy everything heathen? In the Frankish Calendar, March was called Lentzinmanoth.

There is no historical evidence for Eostre in Scandinavia and the April full moon was called Goa in Iceland and Goje in Sweden. All Germanic peoples named their months after the moons.

In her book ‘An Egg for Easter’, Venetia Newell explains that in the 8th and 9th centuries, the expression ‘ostarstuopha’ came into use to denote a Germanic seasonal tribute to the king which suggests an even earlier common use of the word in connection to this time of year. This took place in the Main valley. The Main being the longest tributary of the Rhine river. Interestingly the same region as the Matronae Austriahenae.

Many centuries later Jacob Grimm, of the famed ‘Grimms’ Fairy Tales’, who thought very highly of Bede’s work, published his own book ‘Teutonic Mythology’ in 1835. He theorised that since Bede had said that the Old English for Easter was named after the goddess Eostre, then the similar German ‘ostern’ must also be a forgotten pan-Germanic goddess. In his book, Grimm gives Eostre the name of ‘Ostara’ and calls her a goddess of the dawn, which he derives from the etymology of her name (‘eos’ being the Greek word for dawn). He writes, ‘the divinity of the radiant dawn…whose meaning could easily be adapted to the resurrection day of the Christian God.’ He continues, ‘This Ostara, like the Anglo Saxon Eostre, must in the heathen religion have denoted a higher being, whose worship was so firmly rooted that the Christian teachers tolerated the name and applied it to one of their own grandest anniversaries’. So from the pages of ‘Teutonic Mythology’ Ostara as we know her today was brought into being.

The name ‘ostara’ is actually a plural noun and its singular form is ‘ostarun’ which Grimm explains away by saying that the spring festival lasted for several days. He assumes this is the case because Bede wrote ‘feasts’ and not ‘feast’ when discussing the honouring of Eostre. Grimm also believed that the name ‘Austra’ might have been the female equivalent of ‘Austri’, a dwarf mentioned in the Prose Edda that possibly represented the east wind. He tries his best to connect Ostara with eggs, but gives no evidence for this and also adds that bonfires were lit at Easter.

It is important to remember that the Grimm brothers were nationalists and lived at a time when Germany was not yet a country, but was made up of several different principalities. Their fervent research and writing of myths and folk tales were a way for them to reclaim their ancestral culture which they believed had been lost for centuries under the rule of the Roman Catholic Church. The creation of the modern day ‘Ostara’ was a clever attempt to incite a pagan revival and support a united Germanic mythology.

The only evidence we have of a Germanic ‘spring’ festival is Sigurblot, one of three annual sacrificial feasts, which took place on the full moon around the month of April.

In Ynglinga Saga, chapter 8 it says, ’Odin established the same law in his land that had been in force in Asaland…On winter day (the first day of winter) there should be blot (sacrifice) for a good year, and in the middle of winter for a good crop; and the third blot should be on summer day, a Victory-blot’.

In Heimskringla Olaf Haroldson’s Saga, chapter 76 it says,’ In Sweden there was an age old custom whilst they were still heathen that there should be a blot in Upsala during Goa (April moon). Then they would blot for peace and victory for their king. People from all over Sweden were to resort there.’

Sigurblot took place three full moons after Yule and six full moons after Winter Nights. It was celebrated by the Saxons, the Danes, the Geats, the Swedes, the Icelanders and the Norwegians. This year the festival fall on 6th April until 8th April as historically Germanic festivals lasted for three days and three nights. So could the Anglo Saxons have celebrated a spring festival during April as well? In Germany today, many people celebrate traditions that have been passed down from pre-Christian times. The town of Lugde and its famous Osterrader is one of them.

Historically, the Germanic and Celtic peoples followed a luni-solar calendar and not a solar calendar. Their festivals did not take place on solstices nor equinoxes but on full moons. Even the Anglo Saxon Mothers’ Night would have taken place on a full moon and not on the solar date of Christmas. It just so happened to be a full moon on the Christmas that Bede was actively researching and writing about the Anglo Saxon calendar. We can confidently say that there was no pre-Christian spring festival taking place on the spring equinox and it is also the month of April that is called Eosturmonath not March when the equinox takes place. I talk in more detail about the luni-solar calendar along with ancient time keeping in my Yule post.

Since the nineteenth century, many tales and myths pertaining to the goddess Ostara have been told and sadly there is no great age to them. They are just simply modern day fairy tales. There is no evidence that associates rabbits, hares, eggs or spring with Ostara despite what we have been led to believe.

We have also been misled to believe that the Christian holiday of Easter superseded the ‘pagan festival’ of Ostara and that Christianity is to blame for taking it away from the pre-Christians. From what I have read and understood, the early Christians only took the name of Ostara and never actually replaced a pagan festival because there never was one to replace. Bede insists that it was the English people that wanted to keep the old name (in German it is Ostern) while other European countries accepted the Hebrew ‘Pesach’ meaning Passover (Paques. Pasqua, Paske, Pascua, Pastele etc).

The celebration of Easter long predated the conversion of the Anglo Saxons and the word ‘eostre’ which is commonly found in Old English texts has always meant Passover. It seems that ‘eostre’ had no pagan connotations and if it once did then it was soon forgotten.

Passover is a Jewish spring festival that commemorates the liberation of the Jewish people from slavery in Egypt as told in the book of Exodus in the Bible. It was and still is the most important Jewish festival and because Passover was biblical, the early Christians wanted Easter to take place at around the same time. Passover is celebrated on the fifteenth day of Nisan which is the first month of spring and lasts for eight days.

Easter and Passover were celebrated at the same time until 325 when the Council of Nicaea was convened by the emperor Constantine. Religious leaders wanted to move away from the Hebrew Calendar and instead decided that the date of Easter should be on the first Sunday, after the first full moon, after the spring equinox. If the full moon falls on a Sunday then Easter is celebrated on the following Sunday. Different Christian communities saw the equinoxes occurring on different dates and it was not until the 8th century and much controversy that a standard date was settled upon across the whole of western Europe.

It is important that we remain mindful when reading any book that states opinion as fact. Some writers have great difficulty with staying impartial and their personal beliefs can naturally influence their writing. This can be demonstrated with the origins of painting eggs at Easter. There is no pre-Christian evidence for this custom amongst the Germanic or Celtic peoples. It can however be found in Slavic culture as in the Ukrainian tradition. The tradition of painting eggs was also found in the region of the Mediterranean where Christians painted their eggs red with a cross on them; the red representing the blood of Christ. This would have eventually spread to northern Europe.

The Easter Rabbit or Hare (osterhase) and painted eggs are mentioned in sixteenth century German literature, where it is written that good children were rewarded with painted eggs if they decorated their hats with nests. Eggs were one of the things that Christians were forbidden to eat during Lent, so Easter Sunday would have been an even greater cause for celebration when eggs were abundant once more. This time of year also coincides with chickens laying eggs again after the long winter.

The naming of the modern day spring festival of Ostara happened in the 1970s when an American academic, poet and Wiccan called Aiden Kelly wanted to rename the summer solstice (Litha) autumn equinox (Mabon) and of course the spring equinox so that they would have ‘pagan’ names to go along with the other festivals on the Wiccan Wheel of the Year. He took inspiration from mythology and Victorian and Edwardian Literature.

After all that I have researched, a seed of Eostre’s existence has been planted in my mind. There is a real possibility that she was once a local goddess that was venerated as part of a much larger cult by the Frisians and Franks and later on by the Anglo Saxons, but there is no historical evidence that she was a spring goddess or was even honoured at the vernal equinox along with her eggs and hare. Unsurprisingly, I am left with more questions than answers because everything hinges on Bede. To paraphrase Ronald Hutton, if you take Ostara out of the equation, then there is no pre-Christian spring festival. Our ancestors were far too busy ploughing, sowing and caring for their livestock after a long harsh winter.

Remember, just because something does not fit the typical Christian model does not mean it is pagan.

The wonderful thing about history though is that it is not set in stone and archaeologists are discovering new finds all the time that could change the way we see the past. So who knows, perhaps one day an intrepid metal detector enthusiast will dig up a little figurine of Eostre in the middle of a field in Kent.

What do you think? Is it possible that Eostre was a goddess and also part of a much larger cult? Or has Bede got it all wrong and Eosturmonath is not actually even named after her?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Winters in the World by Eleanor Parker (2022)

An Egg at Easter by Venetia Newall (1971)

The Stone Men of Malekula by John Layard (1942)

The Lady of the Hare by John Layard (1944)

Teutonic Mythology by Jacob Grimm (1835)

Looking for the Lost Gods of England by Kathleen Herbert (1994)

Stations of the Sun by Ronald Hutton (2001)

History of the Goths by Herwig Wolfram (1990)

Life of Charlemagne by Einhard c830 (Chapter 29) free online.

Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World by Philip A Shaw (2011)

The Moon, Myth and Image by Jules Cashford (2003)

Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson (13th century) free online.

The Saga of Icelanders, Penguin Edition (2001)

De Temporum Ratione, chapter 15, by Bede (725) free online.

The Community of the Matronae Cult in the Roman Rhineland, thesis by Kevin Woram (2016) free online.

Thank you for this extraordinary piece of research and writing. It's lovely that you have gathered all of this together in one place and I can only imagine the time that it took! Isn't 'Winters in the World' a most wonderful and helpful book. As for Easter/Ostara, many Pagans are very attached to her I know and so it is a challenge to have any discussion around her (maybe) non-existence. There is also an attachment to those 'nasty Christians'. Christianity has many things to answer for (as do most religions), but stealing Spring festivals isn't one of them.

Living in Kent, I quite like the idea of Eostre being a local deity connected to the the village of Eastry and the land around it. That makes much more sense to me than a goddess who was worshipped across the Anglo-Saxon world but whose existence has completely disappeared, other than Bede's writing of course. What a scamp he was sending us into such disarray!

Thank you again for your wonderful work.