May Day celebrations have their origins rooted in the ancient Roman festival of Floralia which was dedicated to the goddess who presided over fruits, flowers, trees and crops. Flora was known to encompass all aspects of the earth mother including death.

Floralia took place between 28th April and 3rd May and was more than just a flower festival. There were theatrical performances as well as circus games and the festival ended with a sacrifice to Flora which was led by her own Flamen (priest). A circus was a large open-air arena where chariot races and horse races would entertain Roman citizens. Goats and hares were let loose in the circus and beans and lupins were thrown into the crowds. These were all symbols of fertility. An element of the festival took place during the night and it was customary for people to wear brightly coloured clothes. Flora’s cult was widespread across Italy as well as further afield. Some believe that her cult was brought to Britain by Belgic invaders towards the end of the first century B.C.

Going ‘a-Maying’ was enjoyed by those who went out on May Eve or just before dawn on May Day to gather greenery and flowers for the May Day festivities. The sounds of cow horns, drums and May whistles which were crafted from twigs, filled the air with music as they went. There is no historical evidence to support the modern day belief that young couples went in droves to the woods in the middle of the night to ‘consummate’ the union between a pagan god and goddess. If there was a rise in births around the month of February then that may have supported this idea, but in actual fact, the birth rate was highest in July. I don't believe the idea of rolling around in the cold and damp was very appealing to our ancestors! It is important to remember that in the 17th century, Puritans attempted to ban May Day with many of them writing about the partaking of ‘Heathen’ debauchery. Their aim, much like the Roman writings about the Celts, was to grossly exaggerate the ‘wicked’ behaviour of the ‘enemy’ as a means to advance their agenda. Centuries later, the ‘Greenwood Marriage’ has now become a cringe worthy neo-pagan stereotype.

People returned home with baskets full of flowers and tree branches. Small bouquets were hung over doors and windows and posies were tied to carts, horse bridles, cow horns and tails. Even milk pail handles and milk dashes were decorated to protect the milk from being whisked away by the fairies. Crosses made out of twigs and decorated with flowers were hung up in prominent positions and flowers were gifted to the lonely and elderly.

In Ireland, flowers were gathered in honour of the Virgin Mary, as the month of May was dedicated to her. May boughs decorated kitchens, doorsteps, windowsills and roofs of homes as well as byres to ward against evil influences. The most popular trees that were used were birch and larch. Hawthorn branches were also hung up inside the home to protect the household from witches.

Each region had their own superstitions when it came to which trees were lucky and which ones were not. Whitethorn was many people's favourite and was decorated with yellow flowers, ribbons, paper streamers and garlands made of decorated eggs that had been specifically kept aside since Easter. Decorating the May Bough was a family tradition where everyone lent a hand. Rush lights or candles were sometimes attached to the branches which were left outside by the front door until the end of May or until they had all dried up. The dead greenery would then be burnt on the fire. Children went around with their own May Bough collecting money and decorations while singing, “Long life and a pretty wife, and a candle for the May Bush.” On May Eve, a figure called the May Baby was made, very much like a corn dolly, and represented the spirit of spring. It took centre stage at many May Day celebrations.

In the Midlands and the north west of England, young men went ‘May Birching’ on May Eve. Under the cover of night, they left branches in front of the doors of girls they fancied. The most common branches were mountain ash and flowering hawthorn. A girl who was disliked woke up in the morning to find nettles, elder, thistles or thorns on her doorstep. Most of the trees or bushes’ names rhymed with what the young men thought of the girls. For example, briar rhymes with liar, nut with slut, pear with fair and lime with prime! Girls were not the only ones to find a surprise on their doorstep in the morning. A grumpy neighbour might find a branch from a crab apple tree or even worse their doorstep sprinkled with salt. In ‘Celtic’ areas, straw effigies of men or horse skulls were left instead. The tradition of May Birching died out when communities grew so large that people no longer knew one another. May Eve was known as a time of doing mischief and some boys played pranks on those they disliked. Field gates would be left open or fences pulled up.

At dawn on May Day, women of all ages went out and washed their faces in the morning dew. Samuel Pepys wrote that his wife did this every year. It was believed that the dew would ensure a beautiful complexion and good luck. Pieces of cloth would be laid on the grass and wrung out into bottles to be kept as a cure for conditions such as rheumatism and consumption. Blankets soaked in dew were wrapped around children who were sick. Dew from the hawthorn was also seen as very beneficial and in Cornwall the best dew came from the graves of the recently departed. Dew throughout the whole of May was seen as beneficial, but the most potent time was May Day at dawn.

In some areas, the flowering hawthorn determined when May day was to be celebrated.

“The fair maid who on the First of May,

Goes to the fields at break of day,

And washes in dew from the hawthorn tree,

Will ever after handsome be.”

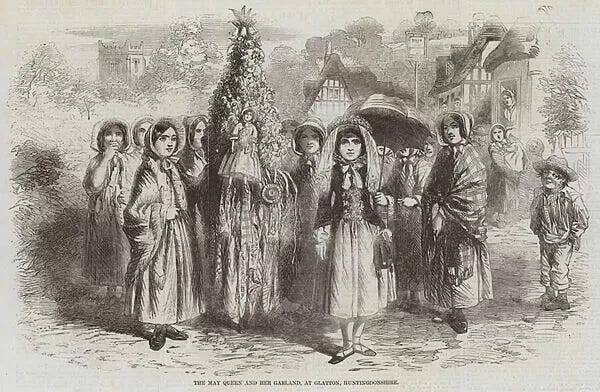

Young girls who were not so worried about their looks made May garlands. They did this by tying two hoops together at right angles and decorating them with leaves and spring flowers. Sometimes a flower or a china doll dressed in white called ‘The Lady’ was placed in the middle, possibly representing a spring goddess or the Virgin Mary. A May garland could also simply be a bunch of flowers tied to the top of a pole or a pole covered with flowers. In some parts of England it was customary for groups of children to carry a May garland in a procession around the village singing and collecting money. Girls were dressed in white and boys wore brightly coloured ribbons and bows along with sashes worn crosswise. A piece of muslin covered the garland until a donation was made. Gifts of meat, fruit, vegetables and herbs were also given to the children.

“Good morning, lords and ladies,

It is the first of May.

We hope you’ll view our garland,

It is so very gay.”

Other children placed a doll inside a box filled with flowers and covered it with some lace or a white handkerchief. They went door to door asking people to lift the cloth for luck in exchange for a gift. The doll was called the ‘Maulkin’ (an interesting meaning of this name can be found on etymology online) and the tradition was common in the south of England. In Buckinghamshire, dolls that represented Mary and Jesus were put in the centre of wreaths.

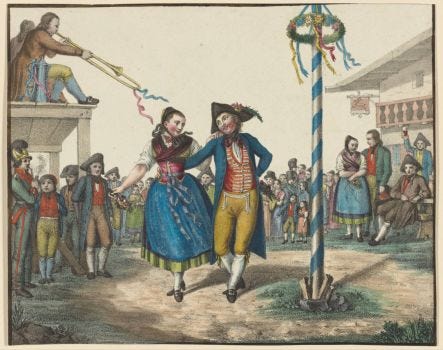

For the rest of the day there was dancing on the village green, archery contests and feats of strength among the men. Milk maids danced around garlands that were decorated with valuable items (see painting below).

Rosemary, rue, blackthorn and hemlock were burnt in the belief that this would drive out evil influences. Rowan and marsh marigolds were worn for protection and it was seen as unlucky to turn any wood into a broom today.

A Suffolk maid who brought her mistress a branch of hawthorn blossom this morning would be gifted a bowl of cream for breakfast. In any other place, bringing a hawthorn branch into the house was to invite misfortune.

Sacred wells were known to grant wishes today and the Pin Well in Wooler, Northumberland was visited by sweethearts. The first person to draw water, known as ‘the cream’, from the well threw flowers into it to show others that they were too late. This water was believed to be the most potent of the year and was used for blessing, cleansing and healing.

The highlight of May Day was the crowning of the May Queen, the human representation of Flora. It was traditional for a beautiful young girl to be seated on a bower decorated with flowers while she watched the festivities. She was not allowed to take part in the fun and an old belief stated that she would die within the year! During the Middle Ages, the May Queen wore white muslin decorated with ribbons and was a young woman not a girl.

The Lord of the May, also known as the ‘May King’ or the ‘May Groom’, was once as important as the May Queen. He wore silk handkerchiefs tied around his legs and arms and carried a sword. Another male figure, a dancing man covered entirely with greenery, was ‘Jack-in-the-Green’ or ‘Jack-in-the-Bush’. In other parts of Europe he was known as ‘Green George’, the ‘Wild Man’, ‘Leaf Man’ or the ‘Green Man’. Jack-in-the-Green can sometimes be seen in old church carvings, often with his face covered with oak and hawthorn leaves. The character feigns sleep or death before magically being woken up. This mysterious figure was bizarrely adopted by chimney sweeps whose annual holiday was on the first of May. Jack-in-the-Green played a prominent role in their processions; a single green figure covered in brightly coloured ribbons and tinsel. It was considered lucky to be kissed by a chimney sweep. The tradition died out in the 19th century after the introduction of the Climbing Boys Act when it was no longer legal to employ young boys as chimney sweeps. There is, however, the Rochester Sweeps Festival in Kent that still takes place every year on the May Bank Holiday weekend.

The most recognisable symbol of May Day is undoubtedly the maypole which was crafted from a tall straight pine, larch, elm, birch or ash tree. The original English maypole was painted with brightly coloured rings and spirals and was erected on the village green or marketplace where it was then decorated with garlands, ribbons and flowers. There are no records of what kind of dances were originally performed around the maypole, but plaiting the maypole’s ribbons originated from southern Europe where maypoles were shorter. This type of maypole was introduced in England in 1880. A maypole could last for many years and was only ever replaced if the base began to rot.

It is unknown when the maypole arrived in the British Isles. The earliest written evidence in England of a maypole was in the 13th century where a charter granted by King John called it a ‘mepul’. A 14th century Welsh poem describes a tall birch tree that was used for a pole around which festivities took place and Geoffrey Chaucer, a 14th century English writer, has a poem that mentions a permanent one in Cornhill, London. Maypoles in the British Isles were only found in England and Wales where early sources describe the May pole as a permanent fixture where people gathered for May Day festivities.

During the reign of Elizabeth I, a Puritan called Philip Stubbs wrote how the maypole (a stinking idol) was drawn by twenty or forty oxen with flowers tied to the tips of their horns. He described the maypole as being decorated with flowers and herbs bound with strings from top to bottom. It was followed in a procession by two to three hundred men, women and children. Once erected, the handkerchiefs and flags that were tied to the top would stream in the wind as everyone danced and leapt around it. This is the only detailed description we have of a maypole in England.

Maypoles became increasingly seen as immoral by the Puritans and during the reign of Edward VI many were destroyed. The most famous of these was the maypole in the Strand, London in 1661 where it had stood for more than fifty years. It was over 130 feet high and was so heavy that it took twelve sailors using pulleys and anchors and four hours to raise it. In 1664, the Ordinance of the Long Parliament forbade any maypole to be erected. May Day as a whole was seen as a ‘heathenish vanity generally abused to superstition and wickedness’.

There is no historical evidence that maypoles were ever associated with pagan beliefs or that they ever represented a phallus. Maypoles were never carved to resemble one and our pre-Christian ancestors would have done so if that was to be what it symbolised. The idea that the maypole was a fertility symbol came from the moral and political philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) who was a Puritan as well as the neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). The neo-pagan religion of Wicca then brought it to modern day paganism. There is no historical evidence either that links the maypole to the Saxons’ sacred tree known as the Irminsul.

Maypoles returned after the end of the Reformation in the second half of the 16th century. A crown was added to the top of them when Charles II returned to the throne in 1660 after the English Civil War along and the death of Oliver Cromwell.

Maypoles often had to be guarded as there was a high possibility that they could be stolen by a neighbouring village who wanted to acquire the good luck that was embodied within it.

Royal Oak Day and Garland Day, which took place at the end of the month, absorbed some of the old May Day traditions which gradually faded away until they were revived again by the Victorians. When a maypole came to the end of its life it was transformed into a house beam or ladder.

A tradition that still survives today is Morris dancing. The first of May was the start date for Morris dances at fairs and festivals which continued through the year until Christmas. There are many theories about its origins. Perhaps it was a Moorish tradition or a tradition brought to England from Spain, France or Belgium. Some believe that the name derives from ‘morisco’, a word which described the Spanish Moors (Arabs living in Spain) or a derivation of Romish from the Romany Culture. Whatever the truth, the dance has characteristic traits of pagan rites, ones that once celebrated the rebirth of spring as well as the fertility of crops and livestock.

Morris dancers who were originally all men wore clothes decorated with scarves, ribbons and lace along with gold rings and precious stones. The ritual dance consists of stamping, leaping, kicking and clapping while waving handkerchiefs in the air to entice young crops grow. Twenty to forty bells attached to each leg tinkle loudly, waking up the sleeping earth spirits as well as a call for collecting alms. Some dances use staves and others use swords. Morris dancers are often accompanied by a hobby horse or a dragon along with Mummers, pipers, drummers, accordions, melodeons, penny whistles and violins. The earliest records of Morris dancing in England are from 15th century royal courts. Puritans called it the ‘Devil’s Dance’.

At the beginning of the 16th century, a Robin Hood play came into being and became part of Morris dancing. The main characters in the play were Robin Hood, a Christianised form of Robin Goodfellow who was a mischievous nature spirit, and Maid Marian who was a much later edition to the play and was associated with the May Queen. During the play Robin dies and comes back to life. Another figure who encourages the crops to grow and the summer to return.

Sword dances were also a part of May Day celebrations. Brought to England from Denmark they were later relics of an ancient tradition that replayed the battle between the old year and the new one. They were usually performed in the winter and involved a sacrifice that returns to life; an ancient belief of survival, sacrifice and rebirth. During the Industrial Revolution these forms of dance gradually faded away as more and more rural communities began to break up.

In Cornwall and other parts of the country there used to be a Hobby Horse Festival held on the first of May. Hobby Horse is a diminutive of Robin Horse, a name that was used for small and medium horses. The Hobby Horse was a strange figure of a man standing inside a hoop. It was covered in a cloth and had a handcrafted horse’s head and tail. Accompanied by singers and musicians, the Hobby Horse would go from house to house with people wishing each other good luck and happiness. Galloping after young women, the Hobby Horse would trap them under his hoop which brought her good luck (luck meaning finding a husband within the year or having plenty of healthy babies if she was already married). Could this be a relic of an ancient pagan fertility rite? At one time, women’s faces or dresses were smeared with black lead or tar from the underside of the cloth (later on it was soot) as part of the ‘initiation’. There was also a rainmaking rite where the Hobby Horse drank from a pool after which he would sprinkle the water over people. This custom died out in the 1930s. In some areas the Hobby Horse feigns death and after being patted he comes back to life again.

There was a strong belief in fairies around this time of year because it was easier to catch a glimpse of the Otherworld. If the Queen of the Fairies was to ride past someone on her pure white horse while they were sitting under a hawthorn tree, it was said that the person had to close their eyes and turn their head away so as not to be lured away for seven long years. The fairies were known to kidnap humans today, especially children who were often substituted for a ‘May Changeling’. To protect their homes from faeries on May Eve, people placed rowan sprigs around their doors and windows as well as on cows’ horns and over the entrance of the cow barn because it was believed that faeries would steal the cows and their milk and butter. Milk was poured around animal dwellings and also onto the roots of a nearby ‘fairy thorn’. Wells, milk and crops could be protected by attaching a rowan twig or piece of iron close by. Bannock cakes, honey, milk and leftover food were often left on the doorstep or at a fairy fort, a lone bush or any other fairy dwelling in the hope of winning the fairies’ favour. Elder leaves were also gathered to protect the house and cuckoo flowers were believed to keep them away. Yellow flowers were believed to offer protection and to guarantee a good yield of butter, so they were scattered around wells and livestock buildings and tied to cows’ tails.

The custom of putting a spent cinder from the hearth or a piece of iron in a pocket to ward against fairies was practiced on May Eve, with a black handled knife being the best form of iron. A sprig of mountain ash twisted into a ring could be looked through to see fairies. ‘The Good Folk’ loved to cause mortals to lose their way by bringing down mists or by ‘moving’ landmarks. To turn one's coat inside out was a good disguise and in turn confused the fairies, thus enabling the person to escape. The fairy stroke, the Anglo Saxon ‘Elf Shot’ took many forms: a sudden injury or illness to humans and cattle as well as bad weather. Prehistoric flint weapons that were thought to be fairy darts could be used as a cure by applying them to the afflicted part or by putting them inside a drinking cup.

May Eve was called Nettlemas Night in Ireland. Young boys would hit each other with bunches of nettles or slyly touch people walking by with them. This is believed to be a custom based on an old cure for rheumatism. In other areas, people were struck with marshmallow plants as it was believed this protected against illness and fairy influence. Folk in Ireland who were concerned for their cattle, placed a cross on the right side of their cow or the cow was plastered with its own excrement which protected it from harm.

Witches were abroad on May Eve, in fact, the whole month was ‘witch-ridden’. In Somerset, a cross shape was drawn onto the hearth’s ashes with a hazel twig and protective marsh marigold and primrose balls were hung over doors of homes and cowsheds as well as charms made from birch and rowan. In Herefordshire, a tall birch sapling called a ‘may pole’ was dressed with red and white streamers and was set up against the stable door to protect the horses from being ‘hag-ridden’ during the night. The pole nullified the effects of witchcraft and would stay there all year protecting against witches and bad luck.

Many centuries previously, the Anglo Saxons called the month of May ‘Thrimilci’, which means the ‘three-milk month’. This would have been the very first time after a long winter that cows could be milked three times a day. It was a grand occasion for our ancestors who could at last have themselves a full larder which signalled the end of having to ration food supplies. For the Anglo Saxons, the summer ran from 9th of May to 6th of August. They had no equivalent to May Day.

‘Now the bright morning star, day’s harbinger,

Comes dancing from the East, and leads with her

The flow’ry May, who from her green lap throws

The yellow cowslip and the pale primrose.

Hail, bounteous May! thou dost inspire

Mirth and youth and fond desire;

Woods and groves are of thy dressing,

Hill and dale doth boast thy blessing.

Thus we salute thee with our early song,

And welcome thee and wish thee long.’ -Milton

Wishing you a lovely festive May Day. Please tag me on Instagram if you have May Day photos to share as I would love to see them. And check out my May Lore highlights on Instagram as I will be sharing lots of May Day charms and superstitions on there.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Religions Of The Roman Empire by John Ferguson (1982)

Religion In Roman Britain by Martin Henig (1984)

Dictionary of Roman Religion by Lesley Adkins And Roy Adkins (1996)

Curious Country Customs by Jeremy Hobson (2007)

Folklore And Customs Of Rural England by Margaret Baker (1975)

English Traditional Customs by Christina Hole (1975)

Traditions, Superstitions And Folk-lore by Charles Hardwick (1872)

A Calendar Of Country Customs by Ralph Whitlock (1978)

British Calendar Customs by A.R Wright (1936)

A Year Of Festivals by Geoffrey Palmer (1972)

The Chronicle Of Folk Customs by Brian Day (1998)

Winters In The World by Eleanor Parker (2022)

A Dictionary Of British Folk Customs by Christina Hole (1979)

Maypoles, Martyrs And Mayhem by Quentin Cooper and Paul Sullivan (1994)

The Stations Of The Sun by Ronald Hutton (1996)

Thank you for dispelling many of the myths associated with this holiday! It’s good to know that it got such a bad reputation from the puritans.